July 27, 2020: UPDATE to Lincoln’s Body, pp. 165-166; p. 366 footnote. 2

The most exciting moment of all for historians is when they discover a document that finally answers a question they’ve been pondering for years. Since 2005, when I began researching Lincoln’s Body in earnest, I’ve wanted to know if there was any truth to the 1916 claim by Washington DC civil rights activist and art historian Freeman Murray that Frederick Douglass had bad-mouthed Thomas Ball’s 1876 “Emancipation” monument, which shows Lincoln standing benignly over a kneeling, newly freed slave. (See Lincoln’s Body, p. 165.) Murray wrote that Douglass had not only criticized the sculpture, but had done so on April 14, 1876, at the very ceremony in Washington DC where he delivered his classic address dedicating the statue.

On that day Douglass spoke of Lincoln to a large gathering of black and white citizens and to a coterie of major officials, including President Grant. It made no sense to me that Douglass, a man of well-developed political judgment and well-oiled diplomatic finesse, would have disparaged the sculpture at that particular event. Moreover, African Americans had themselves raised $17,000 to pay for it. That was the total cost of the sculpture (Congress chipped in to cover the pedestal).

If Douglass disliked it, he had excellent reasons to keep his opinion to himself during this mass celebration. Of course, he could easily have belittled it privately instead. But there was no compelling evidence of that-- not in 1876 and at no subsequent time before his death in 1895. The only evidence supplied by Murray to support Douglass’s public put-down of it was a 1916 letter he’d received from Washington lawyer and civil servant John W. Cromwell-- 40 years after the event. (The relevant part of Cromwell letter is reprinted in Murray’s book; the portion reprinted by Murray is available on the Smithsonian Libraries website: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/emancipationfree00murr. Thanks to Ted Mann of the Wall St. Journal for sending me the link. See p. 366, n. 2 of Lincoln’s Body for my 2015 take on Cromwell’s letter.)

In the letter, Cromwell told Murray he’d attended the 1876 Douglass speech and four decades later had no doubt about the gist of what Douglass had said to the crowd-- something like “[the statue] showed the Negro on his knees when a more manly attitude would have been indicative of freedom.” He was sure Douglass had said it on that day, but he was surprised, looking back at the published text, not to find the disparaging comment. Douglass must, he thought, have uttered it as an aside during the speech. Cromwell was dead sure he’d said it in the full hearing of anyone standing, like him, within 15 feet of Douglass during the entire speech.

I was sure of one thing myself: no single letter like Cromwell’s, written 40 years after an event, and unsupported by the recollections of other witnesses, could be decisive in establishing what words Douglass had said beyond his written text. One of my graduate school teachers at Stanford, Don Fehrenbacher, had literally written the book on this topic-- Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (1991)-- which beseeched historians not to take later memories at face value: many witnesses, with the best intentions in the world, are well known to have mangled the details of things that happened many decades earlier.

Fast forward to 2020, when events conspired to make whatever Douglass said at any time about the Emancipation sculpture an urgent matter. On May 25, 46-year-old George Floyd, a father of five, was killed by white Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin’s unforgiving knee to the neck. Chauvin looked perfectly composed, hand in his pocket, as if this was the most unexceptional policing move in the book. Three other much younger cops looked on, none of them intervening. A teenager’s video of this eight-minute-long “I Can’t Breathe” homicide set in motion a cascading stream of protests taking aim at police brutality and systemic racism. Within a day Chauvin’s breezy insouciance was summing up four centuries of white indifference toward black lives.

In a collective heave of recognition, thousands or millions of white Americans realized anew that they had failed forty-four million fellow citizens subjected to massively disproportionate numbers of police killings, and also to daily indignities for simply “living while black” in America. Many whites and other non-blacks joined African Americans in denouncing all symbols and practices of racial inequality and oppression. Soon dozens of historical monuments all over the U. S. came under siege. Naturally, activists targeted all Confederate images for defacement or immediate destruction. Statues of U. S. presidents who had ever owned slaves met the same fate, including Ulysses Grant, a firm supporter of civil rights while president, whose brief ownership of a single slave in the 1850s led in 2020 to the tearing down of his sculpted likeness in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

Even the Emancipator himself, who had always hated slavery, could not escape the anti-racist outpouring, since the Ball statue in Washington DC showed a newly freed slave placed in an obviously subordinate position to the great white leader. Whatever Ball’s intentions, whatever the sentiments of the African Americans who had paid for it, the sculpture plainly stood, in the protesters’ eyes, for unrelenting white supremacy. On June 25, 2020 a crowd formed around the sculpture, and some speakers urged the toppling of both Lincoln and ex-slave from their lofty perch. Had the federal government not placed barriers around them, and dispatched national guard troops to back them up, the two 144-year-old bronzes might have tumbled to the ground.

Opposed to tearing down the 12-foot high structure, Eleanor Holmes Norton, the non-voting Delegate to Congress from the District of Columbia, argued in a series of tweets for removing it to a museum. It should be relocated, she said, because the newly freed man was depicted in such an obviously dependent position, and because black people in the 1870s hadn’t been asked about its design. They might well have suggested an independent position, making the point of the monument to highlight the new status of freedom, not just the passing moment of chain-breaking. She added a third point, the historical clincher: Frederick Douglass himself, she said, had voiced opposition to the statue of the black man in his dedication speech.

When I read Norton’s claim about Douglass in the New York Times, I sent the paper a Letter to the Editor. There might well be good reasons for removing the Ball statue, I wrote, but so far as we historians knew, Douglass’s alleged displeasure with it was not one of them. He did not say anything about the sculpture in his address, and there was no conclusive evidence that he had ever said anything negative about it, either on that day of dedication in 1876 or at any other time in his life.

Before sending my letter to the Times, I emailed David Blight, the leading authority on Douglass, to be sure that in the years since he and I had first talked about the statue’s dedication no new evidence had come to light-- evidence suggesting that Douglass ever expressed misgivings about it in 1876 or afterwards. Blight confirmed he’d never seen such evidence.

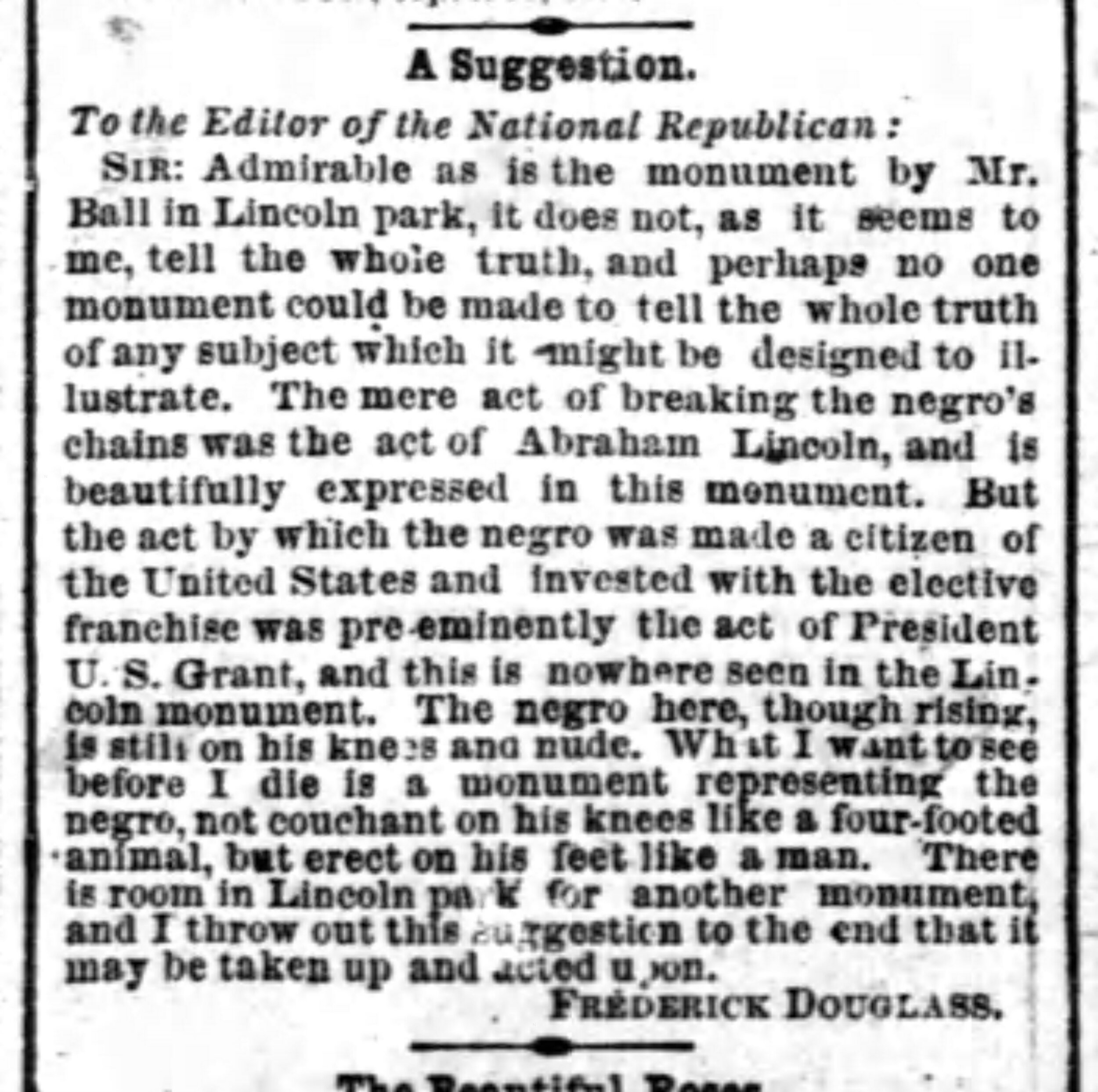

I emailed my letter to the Times on Thursday night, June 25, as a District of Columbia crowd was circling the monument, with some calling for its dismantling on Friday. (The arrival of National Guard troops shut down that plan.) On Saturday morning, June 27, as my letter was being considered at the Times, Blight received an email from another historian well known to both of us, Scott Sandage, and he immediately relayed it to me. That very morning, working independently, with no knowledge of my email discussion with Blight, or of my Letter to the Editor, Sandage had turned up documentary proof of what Douglass thought about the statue in 1876. A mere five days after his April 14 address, Douglass had penned a brief letter to a small Republican newspaper in Washington DC. In it, he said some nice things about the monument, but he finished by gently indicting its depiction of the slave. In light of Douglass’s Letter to the Editor of 1876, I emailed the Times to withdraw my Letter to the Editor of 2020. Fortunately, they hadn’t already run it.

It turns out that what Douglass wrote about Thomas Ball’s slave figure on April 19, 1876 is almost identical to what John Cromwell thought he heard Frederick say on April 14. Maybe Douglass did say it before or after his speech to some small group of listeners-- and said it softly enough that none of the many reporters present could hear what he said, but loud enough for Cromwell and some others to make it out. But I think it’s more likely that Cromwell didn’t hear Douglass express any opinion at all on April 14. I suspect he read Douglass’s Letter to the Editor in the National Republican five days or more later. Impressed by those words, he committed them to memory. Over the next 40 years, he retained phrases close to the exact language Douglass used in his letter. Always recalling their significance, he finally came to believe-- with no conscious deception-- that Douglass had spoken them during his speech. What mattered most to Cromwell was the message Douglass had sent out into the world, not the exact place where the message had originated.

As of June 27, 2020, thanks to Scott Sandage’s swift detective work, Frederick Douglass speaks to us from the grave, urging us now to place a standing African American alongside the kneeling one. A distinguished verbal stylist, he knew many readers-- including President Grant, a gifted writer in his own right-- would infer he wanted a statue of President Grant to one day be erected nearby too.

I’m grateful to Ted Mann for the magnified image of “A Suggestion,” Washington National Republican, April 19, 1876, p. 4, and for the full view of page four, where the letter can be seen near the bottom of Column Two. Its placement reveals its status as simply one among many news notes of April 19; it did not qualify as big news. The story was picked up by many other papers-- at least 14 by Scott Sandage’s count-- but it was always treated as a minor news item, even by Republican papers like the Chicago Tribune (which ran the story on April 25 near the bottom of p. 4, col. 7-- I’ve included it below). Sandage informs me that Democratic papers sometimes printed it to mock Douglass or denigrate Grant.