“Don’t Drown, Massa Abe, for God’s Sake!”

© Richard Wightman Fox 2015

Just a week and a half before his assassination Abraham Lincoln spent a whirlwind two days visiting Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia. He’d already been enjoying himself for over a week at City Point, General Grant’s headquarters on the James River—cruising on the water with his son Tad, rubbing shoulders with the troops, crafting telegrams on the state of the fighting and cabling them back to the War Department in Washington. But the side trips to Petersburg and Richmond seem to have given him a special joy.

Unfortunately for us, he never got the chance to reflect on what those visits of April 3 and 4, 1865 meant to him, or to disclose exactly why he went. We’re left with a few journalists’ dispatches and some later recollections of people who made the trips with him. Those sources are not all equally reliable, but taken together they affirm an undeniable fact: in both cities Lincoln encountered throngs of euphoric African Americans, and the experience moved him deeply.

Imagine the moment for them: this was the first full day of their emancipation on the ground. Union troops had retaken Petersburg on April 2 and Richmond on April 3, putting an end to slavery in those places, though legal emancipation would come later. Many slaves had heralded Lincoln’s name since 1860, and the vast majority cherished by 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation. They turned him into a divinely appointed emissary of American ideals years before most northerners did (after his assassination).

And imagine the moment for Lincoln: having always abhorred slavery, while tolerating it where it was constitutionally protected, he got to savor the sights and sounds of emancipation as an event unfolding in real time. For years he’d been preoccupied with emancipation as a political and military matter. Now it was exploding all around him, with exuberant slaves praising him and Jesus for ending their oppression.

In Petersburg, 15 miles southwest of City Point and 30 miles south of Richmond, the streets were “alive with negroes,” Admiral David Porter later remembered, “crazy to see their savior, as they called the president.” In Richmond, Charles Coffin of the Boston Journal was accidentally standing on the very dock where Lincoln ended up stepping ashore. “There was a sudden shout” from black people nearby, as Coffin wrote that night. “They crowded round the President…Such a hurly-burly—such wild, indescribable ecstatic joy I [had] never witnessed.”

Coffin is a more reliable witness than Porter, since his report was filed immediately. Porter’s memories were published two decades years. Coffin too wrote later accounts, inflating his closeness to the president as the years went by. Memory plays tricks as time passes, and in the recalling of Lincoln the tricks usually magnify the importance of the person doing the remembering.

Admiral David Porter accompanied Lincoln to both Petersburg and Richmond in 1865, and in his 1886 memoir (after he had become an aspiring fiction writer), he couldn’t resist concocting a dramatic scene, complete with detailed dialogue. He remembered a group of 12 black laborers who had knelt before Lincoln on the dock in order “to kiss the hem of his garments.” Porter spun that memory into a carefully scripted and staged event, with Lincoln lecturing the black workers on the proper behavior for citizens of a republic.

“Don’t kneel to me,” Lincoln scolds. “That is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy. I am but God’s humble instrument; but you may rest assured that as long as I live no one shall put a shackle on your limbs, and you shall have all the rights which God has given to every other free citizen of this Republic.”

If Lincoln did deliver such a sermonette just after completing an arduous river journey, Porter couldn’t possibly have remembered the exact language of it. But there’s good reason to doubt that Lincoln made any lofty, well-crafted remarks at this point in his day. If the African Americans on the dock had gotten to hear such a polished and memorable reflection, Charles Coffin would likely have noticed it too and reported it.

Lincoln may have given a short speech to some African Americans later that afternoon at Capitol Square-- during his ride around town in a “carriage-and-four”-- and those remarks may have resembled Porter’s “Don’t kneel to me” speech. A southern white girl named Lelian Cook didn’t hear what Lincoln said at the square, but later that day she wrote in her diary that he had addressed “the colored people” there, “telling them they were free, and had no master now but God."

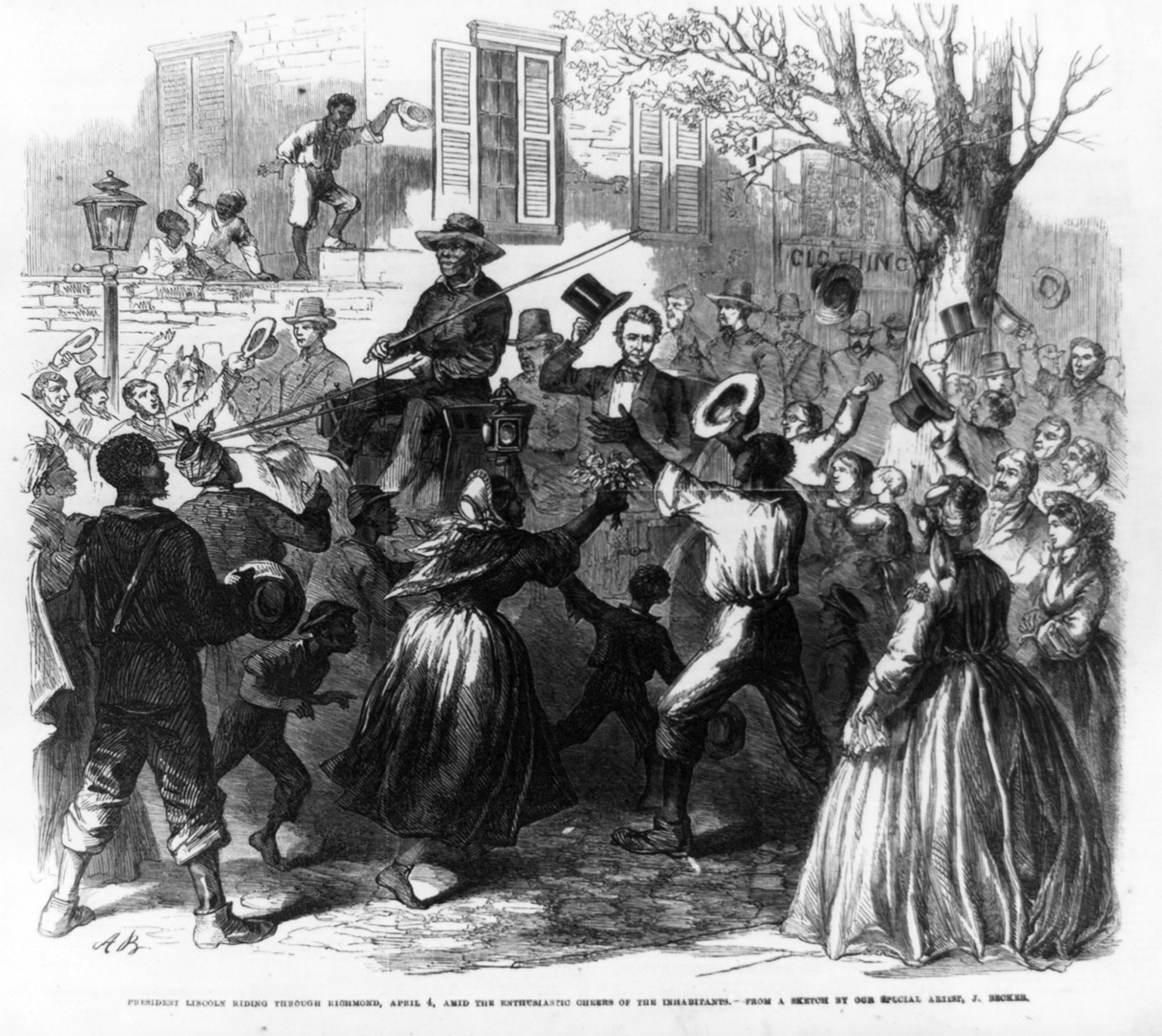

This engraving from the weekly Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (April 22, 1865) shows Lincoln riding off on his city tour (he was escorted by a detail of African-American troops). Note the well-dressed white southerners on the right, implying a warm welcome for Lincoln from everyone in Richmond. But reports in 1865 said the whites in the crowd (one-third of the whole, according to Coffin) were people of modest means. Well-heeled Richmond whites stayed home. By and large, wrote Thomas Morris Chester, an African-American reporter for the Philadelphia Press, they either “stood motionless upon their steps” or “peeped through the window-blinds.”

No artists were on the scene to capture Lincoln’s walk through downtown Richmond earlier in the day, and the absence of visual evidence has facilitated the forgetting of the Richmond trek in our time. But the written evidence is overwhelming: Lincoln’s uphill journey from the 17th Street dock to Union army headquarters amounted to a mass movement of emancipated humanity, with Lincoln towering over the other marchers in his tall silk hat. The ecstatic crowd that swept him up Governor St. to Broad, and out Twelfth to Marshall, included, by Coffin’s later guess, about 2000 African Americans.

One hopes that Lincoln overheard some of the comments made about him that afternoon. “I know that I am free,” an old black woman said in Chester’s presence, “for I have seen Father Abraham and felt him.” Another “good old colored female” offered her hero a giddily protective bit of advice as the day came to a close. She was standing on the wharf when Lincoln boarded a cutter taking him out to David Porter’s flagship on the James River, where would spend the night. The cutter pushed off, the crowd cheered, and she hollered, “Don’t drown, Massa Abe, for God’s sake!”

In his dispatch composed that night, Coffin said Lincoln had indeed been listening to the words that filled the air that day. He told his readers to remember “the jubilant cries, the countenances beaming with unspeakable joy, the tossing up of caps…free men henceforth and forever, their bonds cut asunder in an hour—men from whose limbs the chains fell yesterday morning.” No wonder that Lincoln “felt his soul stirred; that the tears almost came to his eyes as he heard the thanksgivings to God and Jesus, and the blessings uttered for him from thankful hearts.

The Boston Journal published those words on April 10, 1865 (they were widely reprinted in other papers). Five days later Lincoln was dead, primed for a fame that drew on fond memories of his afternoon adventure in Richmond, Virginia.

This piece draws on my two longer published essays about Lincoln’s day in Richmond: “Lincoln’s Practice of Republicanism: Striding Through Richmond on April 4, 1865,” in Thomas A. Horrocks, et al., The Living Lincoln (Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), pp. 131-51, and “A Death Shock to Chivalry, and a Mortal Wound to Caste”: The Story of Tad and Abraham Lincoln in Richmond,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 33:2 (2012), 1-19. See also my forthcoming “Lincoln’s Greatest Escapade: Walking Through Richmond on April 4, 1865,” in Harold Holzer and Sara Vaughn Gabbard, eds., 1865: America Makes War and Peace in Lincoln’s Final Year (Southern Illinois University Press, May 2015). Thanks to historian Mike Gorman of the National Park Service for sharing with me his fine research on Lincoln’s day in Richmond.